Early Chess (600-1100)

Chaturanga (Sanskrit: चतुरङ्ग) is an ancient Indian strategy game and may be the ancestor of chess. Chaturanga is first known from the Gupta Empire (319 to 465 CE) in the Punjab area of India in the 6th century CE.

The Sanskrit word “chaturanga” means “four limbed” or “four arms.” This refers to the four ancient army divisions of infantry, cavalry, elephantry, and chariotry (pawn, knight, bishop, and rook)

Chaturanga is said to have been invented by the wife of Ravana, King of Ceylon, when his capital, Lanka, was besieged by Rama. (source: Falkener, p 119)

Chaturanga was played on an 8x8 uncheckered board, called ashtapada (Sanskrit for spider). The board was also used in other games in which the use of the dices was combined with a game on the board. The ashtapada was identical with our chessboard. (source: Murray, p. 33)

The pieces in chaturanga were (in Sanskrit) Rajah, the king; Mantra, the counselor; Gaja, the elephant (ancestor of the bishop); Asva, the horse; Ratha, the chariot (or roka the boat); and Padati, the infantryman. Pada meant “foot” and the pawn as a foot soldier. (source: Davidson, pp.8-9)

From the beginning, the pawn always captured diagonally. On reaching the last square, he was promoted to mantra, advancement to the weakest of the major pieces. The mantra, although the ancestor of our queen, was then the least powerful of the officer-pieces. When in modern chess the mantra became the queen, strongest piece on the board, the whole face of the game was changed. (Davidson, p. 9)

During the Sanskrit and Indian period, the game was won either by actually capturing the opponent’s king, or by stripping him of all the other pieces. (Davidson, p. 10)

In the 7th century, Chaturanga was adopted as chatrang (Persian: چترنگ), in Sassanid Persia. The names of the pieces were translated from Sanskrit to Persian. So king became shar; the queen (Mantra) became farzin (counselor); the horse (Asva) became asp; the bishop (Gaja or elephant) became pil; the pawn (Padati or foot soldier) became piyadah. The piece called Ratha or Roka by the Hindus was rendered in Persian as rukh, the word for chariot. (source: Davidson, p. 10)

To avoid accidental and premature game endings, the Persians introduced the practices of warnng the player that his Shah (king) was under attack by calling out “shah,” a call from which our word “check” is directly descended when attacking the king. (source: Davidson, p. 22)

The name of the game in most European languages, such as the English word chess, the French echecs, and the Italian scacchi, can be traced back through the Latin plural scaci, to the Arabic and Persian name of the chess king, shah. (source: Murray, p. 26)

The name ‘chess’ was originally derived from the principal piece which the Persians called the Shah, or king. The world ‘mate’ comes from the world mat (meaning ‘dead’), an Arabic, not a Persian word. (source: Gizycki, p. 13)

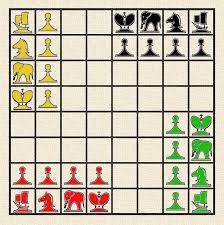

Perhaps the first written evidence of the game of chess appears in the classical Sanskirt romance entitled Vasavadatta (Sanskrit: वासवदत्ता, Vāsavadattā), written by Subandhu (550-620) in the early 7th century. The prose romance tells the popular story of Vasavadatta, the Princess of Ujjayini (daughter of King Pradyota), falling in love with Udayana, King of Vatsa. In describing the rainy season, he wrote, “The time of the rains played its game with frogs for chessmen (nayadyutair) which, yellow and green in color, as if mottled with lac, leapt up on the black field (or garden-bed) squares (koshthika).” (sources: Golombek, p. 11 and Murray, p. 51))

In the 7th century, Arabs conquered Iran and became acquainted with chess. In the world of Islam, chess had to endure a brutal struggle for survival. Some imams tried to ban the game because the Quran forbade the use of images of humans and animals. As a result, the game pieces were changed to abstract shapes. They were made from clay and were inexpensive, which contributed to its spreading among the common people. (sources: Averbakh p. 8)

One of the oldest references to chess is found in the Middle Persian romance called the Karnamak, or the Kar-Namag I Ardashir I Pabagan (Book of the Deeds of Ardeshir, Son of Papak). It was probably written between 590 and 628, during the reign of Khusraw II Parwiz (531-579), the Sasanian king of Persia. It mentions that the hero is skilled in chess. (source: Murray, p. 26) The hero was Artaxerxes (Artakhshir), the founder of the Sassanian dynasty in the 3rd century AD. The story relates how Artakhshir excelled in ball-play, in horsemenship, in chatrang (chess), in hunting, and in other accomplishments. The idea that Artaxerxes played chatrang is a pleasant, romantic buth mythical conception. (source: Golombek, p. 27)

In 625, Banabhatta (Bana) of India wrote Harsah Charitha (The Deeds of Harsha) in Sanskrit. In it, he described the peaceful times of northern India and wrote, “Under this monarch, only the bees quarreled to collect the dew; the only feet cut off were those of measurements, and only from Ashtapada one could learn how to draw up Chaturanga, there were no cutting off the four limbs of condemned criminals.” (source: Golombek, p. 12) It was the first Indian source that mention chaturanga played on the Ashtapada (chess board). This is a poetic work of the author Bana about the life of the king Harsha, ruler of the northwestern India from 606 to 648 AD. (source: Averbakh, p. 20)

Chatrang eventually evolved into the word shatranj (Arabic: شطرنج; Persian: شترنج) in the Muslim world. This occurred after the conquest of Persia by the Rashidun Caliphate. The change of the name was due to the lack of the ch and ng sounds in the Arabic language.

Abu Hurairah (603-681) a companion of Muhammad and the most prolific narrator of hadith, played shatranj. Other companions, such as Abdullah ibn Abbas and Absall bin Zubair are stated to have been seen playing shatranj. (source: Murray, p. 191).

Around 640, the second caliph Omar (reigned from 634 to 644) once saw a game of chess (shatranj), inquired what it was, and was told the legend that chess was invented to console a queen after a civil war between her two sons, whereupon he observed that there was nothing illegal in the game because it was linked with war. (source: Eales, p. 22)

In 656, Ali ibn Abu Talib (600-661), cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad, became caliph and disapproved chess for Muslims. He considered shatranj as the gambling game of non Arabs. His main objection was to the carved chessmen and not to the game itself. He said that it was better to handle a flow (fire) until extinct, than touching chess pieces. Sunnite Muslims use chessmen of conventional pattern. Talib’s son, Husain ibn Ali, is recorded to have played shatranj with his children, and also to have watched a game and to have prompted the players. (Murray p. 191).

Around 660, Amr ibn al-As (573-664) became familiar with chess. He was an Aab commander who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt.

From 685 to 705, Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (646-705) reigned as the 5th Umayyad Caliph. He played shatranj and was the earliest Umayyad caliph associated with chess. (source: Murray, p. 193)

In 665, Sa’id ibn Jubayr (665-714), was born in Africa. He later became an Islamic judge. According to ibn Taimiya, Jubair gave the flowing reason for playing chess. He had reason to believe that al-Hajaj was going to appoint him judge. Fearing that the patronage of al-Hajaj would be detrimental to his piety, he took up chess in order to disqualify himself. Jubair was the first person to be mentioned by name that played chess blindfolded. Jubair turned his back on the board and asked his slave to make the moves for him. Later, al-Hajjaj put him to death for taking part in a revolt. (source: Murray, p. 192)

In 710 al-Walid I (668-715), an Umayyad caliph, killed a shatranj player when the player purposely played poorly against him. Walid was playing shatranj with Abdallah ibn Muawiyah when a Syrian visitor was announced. The caliph ordered a slave to cover over the board, and the visitor was allowed to enter. Walid then discovered the visitor was not knowledgeable in Muslim religion, so he uncovered the board and resumed his game. (sources: Murray, p. 193, Forbes, p. 169, and Four Essays on Art and Literature in Islam by Rosenthal, p. 86)

In Asia, a game similar to chess spread out, moving from India north and eventually giving birth to xiangqi (Chinese chess), trying keui (Korean chess), and shogi (Japanese chess). In all of these versions, the pieces were placed in the intersections of lines rather than inside squares. Later, chess swept through Southeast Asia piggybacked on Buddhism. Religion, Ghengis Khan, and Western colonization assisted the spread, including into Russia. (source: Hallman, p. 43)

Around 720, al-Farazdaq (641-728) wrote Naqa-id Jarir. It mentioned baidaq (foot soldier or pawn) and alluded to pawn promotion. The manuscript gave us enough information to assume that shatrang was generally familiar to his readers. (source: Cazaux p. 16)

In 750, chess came to China from India. Chess is mentioned in the Book of Marvels (written about 800, but only made public in 1088). The Chinese made significant changes to the game and called it Siang K’i. It is played on a board of 9 by 10 lines. The pieces (round discs with characters on the upper surface) are placed on the intersection points instead of the squares. There is a river added to the middle. (source: Divinsky, p. 47)

Muhammad ibn Abdallah al-Mahdi (744-785) was the third Abbasid Caliph. He disapproved of shatranj. In 780 he wrote a letter to the people of Mecca to stop playing shatranj, along with nard, playing with dice, and archery. He considered these vanities that led astray and from the remembrance of Allah. However, chess was played in his court. (Murray, p. 195)

The earliest mention of chess in Chinese literature dates from the 8th century. It supports the theory of an Indian origin. (source: Gizycki, p. 12)

In the late 8th century, chess made it to Greece and became the Greek ‘zatrikion.’ It then reached the Byzantine Empire. Later, zatrikion fell into disrepute in Byzantium ss a sort of Bohemian way of passing the time, stemming from Persian debauchery. Persian luxury was a sort of refined lechery. Chess was associated with other notorious features of Persian luxury. (Golombek, p. 28)

In the early 9th century, the Kashmiri poet Rudrata wrote a poem called Kavyalankara (“the ornaments of Poetry), describing how all the chess pieces move. It also had the earliest example of a knight’s tour.

Harun al-Rashid (763-809) was the fifth Abbasid caliph. He was a chess (shatranj) player who granted good chess players pensions. In 802, Harun supposedly sent Charlemagne a variety of presents, including chessmen. Harun also wrote a letter to Nicephorus of Byzantium (died in 811) in 802 mentioning shatranj. (source: Murray, p. 195)

In 813, an apocryphal story claims that at a critical point in the Siege of Baghdad, Muhammad al-Amin, 6th caliph of the Abbasid Empire, was playing a game of chess against his favorite eunuch, Kauther. A messenger came in during the time he was playing chess, saying the Baghdad’s capture was imminent. Al-Amin told the messenger to be patient, he was about to win his game of chess. Not long after this, al-Amin and his men were captured. The 6th Abbasid caliph, victor in his final chess game, was swiftly beheaded. (sources: Shenk, p. 3 and Murray p. 197)

In 822, chess was introduced at the court of Cordoba, the seat of Spanish Islam, by an influential musician from Baghdad named Ziryab (789-857), also known as Abul-Hasan Ali ibn Nafi. By 950, chess figured prominently in Islamic Spain. Muslims, Christians, and Jews played the game together, the women as well as the men. (source: Yalom, p. 11)

Around 820, Jabir as-Kufi, Rabrab, and Abun-Naan were considered the strongest shatrang players in the Arab world.

Around 840, Caliph al-Mu’tasim Billah (796-842) of Baghdad, also known as Abu IshaqMuhammad ibn Harun ar-Rashi, authored the earliest surviving chess problem book. (source: Wonning, p. 2)

In 842, Al-Adli al-Rumi (800-870) authored one of the first treatises on Shatranj, called Kitab ash-shatranj (Book of Shatranj). He was recognized as the best Shatranj player (aliyat) in the 9th century. In his treatise, he compiled the ideas of his predecessors on Shatranj. The book was lost but the chess problems, endgames, and openings he discussed survived in the works of successors. He also mentioned using a chessboard as an abacus, as a tool to perform mathematical calculations based on the new Indian numerals. He lived during the reign of Caliph Mutawakkil. (source: Shenk, p. 19) He was patronized by a son of Harun ar-Rashid and other Caliphs (al-Wathiq and al-Mutawakki). His name suggests that he came from some part of the eastern Roman Empire, possibly Turkey (source: Hooper p. 2)

In 845, ar-Razi wrote Latif fi-sh shatranj (Elegence in Shatranj), which was a book of

shatranj problems. He also wrote Kitab ash-shatrang (Book of Shatranj).

In 848, al-Adli was defeated in a shatranj match by ar-Razi in front of Caliph al-Mutawakkil in Baghdad.

Al-Adli was the first person to classify chess players. He recognized five classes of players. The highest contained aliyat (grandmasters). The second class was called mutaqaribat or proximes. The third class consisted of the highest class could give odds of a pawn. The fourth class, the highest class could give odds of a knight. The fifth class, the highest class could give odds of a rook. (source: Forbes, p. 104)

Al-Adli was the first to categorize openings into positions called tabiya (battle array). Some of the opening names were: the goat-peg, Pharaoh’s stones, the old women, the wing or flank opening, the torrent, the sheikh's opening, the strongly built opening, the sword, the slave's banner, the army opening, and the shoulder.

Al-Adli was the first to compile chess problems, called mansubat (position). He divided his collection into won endings, drawn endings, and undecided problems.

Al-Adli may have been the first to use coordinates to record positions and moves in chess. He may have also been the first to discover the knight’s tour. His manuscript contained diagrams which represents a knight’s tour on a chess board.

A-Adli described a variation of chess played with dice. This is the earliest instance of the use of die to determine the moves of a form of chess.

The pieces of Shatrang were the Shah (King), Ferzan or Firz (Counselor or today’s Queen), Fil (Elephant or today’s Bishop), Faras (meaning horse; today’s knight), Rukhkh (Rook), and Baidaq (meaning foot soldier; today’s Pawn). The sides were any two colors, most often red versus green, sometimes red versus black. (source: Cazaux, p. 9-10)

In the 9th century, Abdallah ibn al_Mutazz (861-908), the son of caliph al-Mutazz, was a keen chess player. When he played chess, he wanted no interruptions. Once a messenger arrived bearing good news that his chief rival, Al-Mustain, had been defeated. The messenger also brought the severed head of Al-Mustain. Al-Mutazz took no notice, but continued playng until he had finished the game. (source: Golombek, p. 33)

In the 9th century, chess came to Russia directly from the East. The names of the men to this day indicate Persian-Arabian origins. The queen, “fyerzh,” in Russian is a derivative of “vizier.” The bishop is slon (elephant) and the rook is ladia (Boat). There is one theory that chess was brought o Russia by the Tartars. Another theory was that chess was brought into Russia by the Teutonic Knights. (source: Gizycki, p. 16).

In 892 al-Mu’tadid bi-llah (854-902) came to power as the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad. He was a chess player. However, when he discovered that his servants were playing chess rather than doing their duties, they were given several lashes with the whip. (source: Murray, p. 199 and Gambling in Islam by Rosenthal, 1975, p. 145).

In 899, the Spanish Benedictine monk Saint Genadio (the Bishop of Astorga) was a founder of a monastery in El Bierzo and often played chess with the monks. He is the first saint to have his name associated with chess. (Averbakh, p. 46)

By 900, chess was introduced into Europe by the Muslims, probably both by the Moors in Spain and by Saracen traders in Italy. It steadily increased in popularity in spite of some initial opposition from the Church, which considered chess a gambling game, and therefore sinful. (source: Wilson, p. 1)

Around 900, the Chinese Book of Marvels (Huan Kwai Lu) was written and contained the first reference to Chinese chess (xiangqi). (source: Wonning, p. 3)

In 902, al-Muktafi (878-908) came to power as the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad. He took into a favor a shatranj player named al-Mawardi. Then al-Muktafi heard about another shatranj player named Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Yahya as-Suli (880-946), so the caliph arranged a match between the two shatranj players. Around 905, as-Suli defeated al-Mawardi in front of the caliph to become the so-called world shatranj (chess) champion. After al-Mawardi lost, the caliph said to him, “Your rose water has turned to urine.” (Murray, p. 199).

In 902, as-Suli became the leading chess player at the Abbasid court in the reign of Caliph al-Muktafi. As-Suli died in 946. His pupil was al-Lajlaj, who died about 970. As-Suli was a member of a Turkish princely family and a successful courtier, who wrote a literary history of the Abbasid caliphate, as well as works on chess. (source: Eales, p. 20)

By the 10th and 11th century, the game was taken up by the Muslim world after the early Arab Muslims conquered the Sassanid Empire, with the pieces largely keeping their Persian names. The Moors of North Africa rendered the Persian term "shatranj" as shaṭerej, which gave rise to the Spanish acedrex, axedrez and ajedrez; in Portuguese it became xadrez, and in the Greek language zatrikion (ζατρίκιον). In the rest of Europe it was replaced by versions of the Persian shāh ("king"). The game came to be called lūdus scacc(h)ōrum or scacc(h)ī in Latin, scacchi in Italian, escacs in Catalan, échecs in French (or Old French eschecs), schaken in Dutch, Schach in German, szachy in Polish, šahs in Latvian, skak in

Danish, sjakk in Norwegian, schack in Swedish, šakki in Finnish, šah in South Slavic languages sakk in Hungarian and şah in Romanian. Chess spread directly from the Middle East to Russia, where chess became known as шахматы (shakhmaty).

About 950, the Arabic historian al-Masudi, wrote about some observations in chess in India. He wrote that the most frequent use of ivory was for the manufacture of men for chess. When the Indians played chess, they wagered items or precious stones. Sometimes, when a player had lost all his possessions, he would wager one of his limbs. If a man wagered one of his fingers and lost, he would cut off the finger with a dagger, and then plunge his hand in a small copper vessel filled with an ointment over a wood fire to cauterize the wound. (source: Murray, p. 37)

In 970, a Greek, named Jusuph Tchelebi played chess blindfolded in Tripoli. The chess men which he used were large. He played, not by naming the moves, but by feeling the chess men and placing them in the squares, or taking them off, as occasion required. This is the first recorded successful blindfold game of chess. (source:Pruen, p. 53)

Around 980, 18 Arabic bone chess pieces were thrown in a Roman grave at Venafro (between Rome and Naples). They were found in 1932 and examined and carbon-dated in Italian laboratories. The chess pieces are now preserved in the Archaeological Museum in Naples. (source: Monte, p. 5)

In 988, Ibn an-Nadim cataloged all known Arabic books up to that time in his book Kitab al-Fihrist. He wrote of the whole succession of leading players who had composed books or manuscripts on chess. Al-Aldi and ar-Razi were players earlier than as-Suli. The two of them played together before the Caliph al-Mutawakkil (847-861). Al-Adli al-Rumi has established himself as the champion player until he lost to the younger ar-Razi. (source: Eales, p. 20)

In the late 990s, a Medieval Latin poem of 98 lines about chess, the Versus de scacchis (Verses on Chess ) was written and later preserved in the Einsiedeln Monastery, Switzerland. The poem contains both the first European description of chess and the first evidence that the chess queen had been born. (source: Yalom, p. 15)

In the 10th century. Several Arab stories were added to the Arabian Nights. One of these stories tells how Caliph Harun al-Rashad paid ten thousand dinars for a slave girl known to be a fine chess player. After ha had lost to her three times in succession, he rewarded her by commuting the sentence of a certain Ahmad ivn al-Amin, presumably her lover. (source: Yalom, p. 9)

At the end of the 10th century, legend has it that the Croatian King Svetoslav Surinj (Stjepan Drzislav) was captured in war. A chess challenge was made and he had the right to rule the Dalmation towns on the Adriatic if he could beat the Venetian Doge, Peter II, in a chess match. The Croation king won and was released from prison to return to Croatia. As a thank you for his freedom, the Croatian king decided to choose a chessboard for his coat of arms. A chessboard appears in the Creation coat of arms. (Shenk, p. 49)

By the year 1000, there were Indian varieties of chess in existence both for two and for four players. In the two-handed game the King and his Minister were added. In the four-handed game, there was only the King and no Minister. The presence of a Minister in a war-game was justified from Sanskrit discussion of his function. (source: Murray, p. 45)

By 1000, chess made its way into the region of ancient Kiev, the oldest of Russian states. Kiev laid on the regularly used Viking trade routes. The Vikings carried chess piees in the area. (source: Buehrer, p. 24)

Around 1000, the vizier was being replaced by a new piece, the queen. By 1200, she could be found all over Western Europe, from Italy to Norway. (source Yalom, p. XVII)

In 1005, chess was banned in Egypt by Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (985-1021). All chess sets were burned in his territory. The order did not extend to the magnificent chess sets in the palace treasury, made of gold, silver, ivory and ebony. But it was too late to stop the game’s march across North Africa. Muslim players were playing chess in Cairo, Tripoli, Sicily, Seville, and Cordoba. (source: Murray, p. 202)

In the 11th century, the great Persian poet Abul-Qasem Ferdowsi Tusi (940-1020) wrote in Shahnama (Book of Kings) how a son invented chess to console his mother, the queen, on the death in battle of his brother, her favorite son. (source: Golombek, p. 10) In one of his poems, he tells of the arrival of envoys of an Indian rajah at the Court of the Persian Shah Chosroes I bringing gifts which include a game depicting a battle of two armies. (source: Gizycki, p. 11) The great epic poem consisted of 120,000 lines.

In the 11th century, Abu ‘l-fath Ahmad as-Sinjari was a chess author where three copies of his chess manuscript were discovered in 1951. He wrote a chess manuscript containing 287 mansubat (chess problems). The surviving copies of his manuscript, made in the Tadzhik language, indicate that he came from Sistan, a land on the eastern border of Iran. (source: Hooper, p. 1)

In the 11th century, archaeological finds showed that chess was played almost everywhere in Europe. At first, it was a part of the knights’ training, but then spread among commoners. (source: Averbakh, p. 8)

In the 11th century, chess reached Bohemia, brought from Italy by wandering Bohemian merchants. Chess also reached Scandinavia. (source: Gizycki, p. 16)

On July 28, 1008, the Catalonian Testament was written by Ermengol I, Count of Urgell (974-1010). He wrote, “I order you, my executors, to give my chessmen to the convent of St. Giles, for the work of the church. This was the first reference to chess in the Christian world and in Western Europe. (sources: Gizycki, p. 15 and Murray, p. 405)

The 17 chess pieces found in Urgell were 8 pawns, a rook, 3 knights, 2 bishops and 3 kings. They were all carved out of quartz and had typical abstract Muslim forms. The sets belonged to Emengol and his brother, Count Ramon Borrell II (who did in 993). After Armengol was killed during a military campaign against Cordoba, his chess pieces were given to the Benedictine monastery of Saint Egidio, located in the south of France. (source: Averbakh, p. 47)

In 1027, Canute (995-1035), king of Denmark and England, learned how to play chess after a pilgrimage to Rome. In 1027, King Canute (Knut) played a game of chess against Jarl (Earl) Ulf at Roskilde. The game ended with a quarrel and the murder of Ulf. The account was found in the prose Edda, written in 1222 by Icelandic poet and historian Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241). It was the first mention of chess in the Norse lands. (source: Monte, p. 10)

Around 1030, the Benedictine monk Froumund von Tegernsee wrote a Latin poem, ‘Ruodlieb.’ This was the earliest reference of chess (ludus scachorum in Latin) in German literature. The poem is one of the earliest romances of knightly adventure. A knight was in the company of an enemy king, which he beat at chess. (source: Gizycki, p. 15)

In 1031, Abu Rayhab Muhammad ibn Ahmad Al-Biruni (973-1050) wrote India, which had a description of chaturaji. He was the first to describe the Indian war game for four players played with a pair of dice. For complete victory in the game for 4 players, it was necessary to keep one’s king and to capture the opponents’ kings. (sources: Averbakh, pp. 20, 23 and Murray p. 58)

In 1058, Countess Ermessind (Ermengaud) willed her chess pieces to the church of St. Giles. The chess pices were specifically said to be made of crystal. (sourcs: Eales, p. 43 and Murray p. 406)

In 1062, the first Italian reference to chess appeared in a letter from the Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia, Peter Damian (1007-1072) to the newly elected Pope Alexander II (1010-1073) reporting that the Bishop of Florence was indulging in secular frivolities such as chess. He assigned the bishop of reading the complete book of Psalms three times, to wash the feet of 12 poor men, and to give to each a piece of money, when he caught him playing the game. (source: Davidson, p. 129)

In the 11th century, France’s first woman poet, Marie de France, described a chess scene in her romance poem Eliduc. This was a story of a knight named Eliduc who lives in Brittany and is loyal to the king. The king plays chess with a foreign guest. This was one of the first metaphors using the game of chess, a “chess morality.” It marked the transition between the Muslim game and its varieties in Western Europe. (source: Gizycki, p. 15)

In 1071, Arnau Mir de Tost listed his collection of 13 chess sets as part of his assets before he went on a pilgrimage.

In 1083, King Vratislav II (1032-1092) of

Bohemia presented a chessboard and ivory and crystal chess set as a wedding

gift for his daughter Judith and her new husband Wiprecht. (source: Monte, p. 7)

References:

Allen, “Chess in Europe during the 18th

Century,” New Monthly Magazine, 1822

Averbakh, A

History of Chess from Chaturanga to the Present Day, 2012

Barrington, “An Historical Disquistion of the

Game of Chess,” Archaeologia, 1787,

ix, 14-38

Bell, Board

and Table Games From Many Civilizations, 1969

Bird, Chess History and Reminiscences, 1908

Bland, On

the Persian Game of Chess, 1852

Brace, An

Illustrated Dictionary of Chess, 1977

Branch, “A Sketch of Chess History,” British Chess Magazine, 1899

Brunet y Bellet, El Ajedrez, 1890

Bueher, Fnkenzrllrt, & Ziejr, Chess, 1989

Calvo, Valencia

Spain: The Cradke of European Chess, 2006

Cazaux & Knowlton, A World of Chess, 2017

Culin, Chess

and Playing-Cards, 1898

Davidson, A

Short History of Chess, 1949

Divinsky, Chess

Encyclopedia, 1990

Eales, Chess, The History of a Game, 1985

Falkener, Games

Ancient and Oriental, 1892

Fiske, Chess

in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature, 1905

Forbes, History

of Chess, 1860

Gizycki, A

History of Chess, 1972

Gollon, Chess

Variations, 1968

Golombek, A

History of Chess, 1976

Golombek, Golombek’s

Encyclopedia of Chess, 1977

Hallman, The

Chess Artist, 2003

Harmon, Chess: Learn about Chess, Its History, Early Tactics, 2021

Hartston, The

Kings of Chess, 1985

Hooper & Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, 1984

Hooper & Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, 2nd edition, 1992

Hyde, Mandragorias

seu Historia Shahiludi, 1694

Keats, Chess

in Jewish History and Hebrew Literature, 1995

Leoncini, La

Storia Degli Scacchi (The History of Chess)

Li, Genealogy

of Chess, 1998

Linder, Chess

in Old Russia, 1979

Linder, The

Art of Chess Pieces, 1994

Maryhill Museum of Art, Chess Sets: A Brief History

Monte, The

Classical Era of Modern Chess, 2014

Murray, A

History of Chess, 1913

Murray, A

Short History of Chess, 1903

Negri, On

the Origins of Chess, 2020 (ChessBase Chess News)

O’Sullivan, Chess in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age, 2012

Pruen, An

Introduction to the History and Study of Chess, 1804

Raabenstein & Samec, Chess in Art: History of Chess in Paintings 1100-1900, 2020

Saunders, How

to Play Winning Chess, 2007

Savenkov, Evolution

of the Game of Chess, 1905

Schonberg, Grandmasters

of Chess, 1973

Sharples, A

Cultural History of Chess-Players, 2017

Shenk, The

Immortal Game: A History of Chess, 2006

Sunnucks, The

Encyclopedia of Chess, 1970

Twiss Chess,

1787

Van der Linde, Geschichte und Litteratur des Schachspiels, 1874

Van der Linde, Quellenstudien, 1881

Von der Lasa, Zur Geschichte und Literatur des Schachspiels, 1897

Wall, Chess

Encyclopedia, 1999

Wall, Chess

From A to Z, 2014

Wall, Oddities

in Chess, 2020

Westerveld, The Virgin Mary: The Association of the Virgin Mary with the French

Chess Piece “Dame,” 2015

Wichmann, Chess: The Story of Chesspieces from Antiquity to Modern Times, 1964

Wilson, A

Picture History of Chess, 1981

Winter, Chess

Notes

Wonning, A

Short History of the Game of Chess, 2014

Yalom, Birth

of the Chess Queen, 2005

Comments

Post a Comment